I'll reiterate at this point that I'm all for reducing income inequality (as well as other forms of inequality), I think it is responsible for a number of pernicious and harmful effects in our society. However, I think the specific take on this problem by Wilkinson & Pickett (W&P) is both objectively unproven (and speculative) and potentially counterproductive.

Neo-materialism and income inequality

Cards on the table, I would probably favour more of a 'neo-materialist' explanation for the ill effects of inequality on society (and particularly on the poor), that is inequality largely has negative consequences through physical and material differences between the lives of the rich and poor. A nice summary of that position is given here:

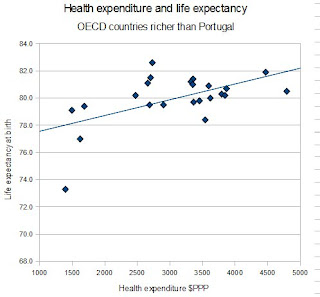

The neo-material interpretation says that health inequalities result from the differential accumulation of exposures and experiences that have their sources in the material world. Under a neo-material interpretation, the effect of income inequality on health reflects a combination of negative exposures and lack of resources held by individuals, along with systematic underinvestment across a wide range of human, physical, health, and social infrastructure. An unequal income distribution is one result of historical, cultural, and political-economic processes. These processes influence the private resources available to individuals and shape the nature of public infrastructure—education, health services, transportation, environmental controls, availability of food, quality of housing, occupational health regulations—that form the “neo-material” matrix of contemporary life.This leads me to object to the core thesis of the Spirit Level - Wilkinson & Pickett go to great pains to claim that far from it being life's material inequalities that underlie the detrimental effects of income inequality in richer societies, it is in fact the psychological impact of this inequality that causes all the problems. Indeed they claim that material inequalities actually have no effect on health or other outcomes! We saw a little of this in part 1 where I discussed W&P's argument that expenditure on health in rich countries actually has no effect at all on life expectancy, infant mortality, or other commonly used measures of health outcome.

Psychosocial effects on health

Although it is a little more vague and spread out in the book, in their interviews for the radio (e.g. Pickett on More or Less, or W&P on Analysis) W&P make it very clear that they are proposing a rather bold version of 'status anxiety' such that the stress of an unequal society directly causes ill effects via the physical consequences of stress hormones on health.

I should be upfront and say that this is far from biologically implausible, we know that chronic stress affects the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis and can therefore alter hormone levels, and we know high levels of the 'stress hormone' cortisol have been associated with increased cardiovascular (but not other) mortality**. But what is so appealing about the psychosocial hypothesis over the neo-materialist explanation for the relationship between income inequality, health, and other bad stuff?

In the Spirit Level W&P say:

As societies have become richer...so the diseases we suffer from and the most important causes of health and illness have changed...During the greater part of the twentieth century, the predominant approach to improving the health of populations was through 'lifestyle choices' and 'risk factors' to prevent these chronic conditions. Smoking, high-fat diets, exercise and alcohol were the focus of attention.The Whitehall II Study

But in the later part of the twentieth century, researchers began to make some surprising discoveries about the determinants of health. They had started to believe that stress was a cause of chronic disease, particularly heart disease. Heart disease was then thought of as the executive's disease, caused by the excess stress experienced by businessmen in responsible positions. The Whitehall I Study, a long-term follow-up study of make civil servants...expected to find the highest risk of heart disease among men in the highest status jobs; instead, they found a strong inverse association between position in the civil service hierachy and death rates...Further studies...in Whitehall II, which included women, have shown that low job status is not only related to a higher risk of heart disease: it is also related to some cancers, chronic lung disease, gastrointestinal disease, depression, suicide, sickness absence from work, back pain and self-reported health.

So was it low status itself that was causing worse health, or could these relationships be explained by differences in lifestyle between civil servants in different grades?..these risk factors explained only one-third of their increased risk of death from heart disease. And of course factors such as absolute poverty and unemployment cannot explain the findings because everybody in these studies was in paid employment. Of all the factors that the Whitehall researchers have studied over the years, job stress and people's sense of control over their work seem to make the most difference.

Ah, the Whitehall II study - it all comes down to this. It is important for W&P to point towards studies like this because, for all their emphasis on comparing countries, because there are so many confounding factors comparing a few dozen heterogeneous countries, no one is going to believe that there is an association between inequality and health unless it can be shown at the individual level within a society.

Putting aside the rather poor history of associations between 'stress' and ill-health*, as W&P say, the finding that cardiovascular disease (CVD) showed an inverse association with job grade in the Whitehall studies was indeed a revolutionary moment in epidemiology. A huge number of publications have emerged from the Whitehall data and the central message has been, as W&P state in the book, that the relationship between job grade and CVD is mediated directly via job stress and control. These findings from the Whitehall II study form the core of the psychosocial explanation for the relationship between income inequality and health. Back in 2001 Wilkinson was saying:

The Whitehall II study showed that low control in the workplace predicted coronary heart disease independent of social status, and that low control in the workplace accounted for about half of the social gradient in cardiovascular diseaseNow the Whitehall II study is something I've covered before, but I think it is clear that my observations merit repetition in the context of the argument over the Spirit Level.

As W&P say, the Whitehall II built on the findings of the Whitehall I study to show that employment grade and health outcomes, in particular coronary heart disease (CHD), are associated***. While risk factors such as smoking do account for a lot of this association it has been claimed that the strongest predictor of CHD incidence, even taking risk factors into account, is 'low control at work'. Job control is supposedly associated with CHD independent of job grade (and so presumably socioeconomic status), leading to the conclusion that low job grade is associated with heart disease because low job grade is associated with low job control - that is, it is the psychosocial strains of being in a low grade job that cause CHD. It would be difficult to overstate just how influential this conclusion from the Whitehall II data has been - although there have been other studies in other populations and looking at other psychosocial factors this is the core of the evidence for the role of psychosocial factors in causing disease.

So just what constitutes coronary heart disease?

The question I want to ask is how robust is this association between CHD and job control? There have been a number of studies looking at the Whitehall II data and job control (e.g. Bosma et al 1997, Kuper & Marmot 2003) and all have found the same thing - low job control is associated with higher incidence of CHD whatever job grade you are in.

But all is not quite as it seems - coronary heart disease (CHD) is quite a broad term, it covers a spectrum from fatal myocardial infarction (MI) to cardiac chest pain (angina), but all of these are the result of ischaemia in the heart. Most studies of the Whitehall II data have tended to lump all CHD together, combining MIs with angina to create the broad category of CHD. If we look at the findings from these studies we can see something very interesting, once we take into account confounding factors (like age or health related behaviours such as smoking) the association between CHD and job control is driven by angina rather than MI.

So in the paper by Kuper & Marmot they looked at two outcomes, all coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction (fatal or non-fatal). They actually found no effect of job control for women, but for men there was a highly significant effect of job control on all CHD even adjusted for coronary risk factors (smoking, cholesterol, hypertension, exercise, alcohol, BMI). However, there was no effect of job control on the rate of MI. And there wasn't even a relationship when the comparison was unadjusted for coronary risk factors. This is a puzzling result - if job control causes CHD then we would expect this to be reflected in all forms of CHD, in rates of MI just as much as angina since it is the same underlying biological process (furring up of the coronary vessels in the heart) that underlies both angina and MI.

If we look at the earlier study by Bosma et al we can begin to see why this anomaly might arise. In the same way as Kuper & Marmot they found an association between job control and all CHD - but they also split the data up into those with angina detected on a questionnaire (the Rose angina questionnaire) and those with CHD diagnosed by a doctor. What they found was that if you controlled for age, sex and coronary risk factors only questionnaire detected angina was associated with job control (with about twice the rate of angina in those with low job control versus those with high control) whereas in those with physician diagnosed CHD there was no statistically significant relationship (and around 1.3x the rate of diagnosed CHD in the low job control group).*4

Since the majority of patients classified as having CHD in the Whitehall II studies had Rose questionnaire diagnosed angina it is these patients driving the association between job control and CHD - those patients with harder end-points, actually having an MI or having a doctor diagnose them with CHD, didn't seem to show this relationship. So why might that be?

Diagnosis by questionnaire

The Rose angina questionnaire used in the Whitehall II study is a self reported measure of chest pain. All studies that have looked at the association between psychosocial factors and CHD in the Whitehall II data have classified anyone with a positive angina questionnaire as having angina and thus having CHD. The use of this questionnaire reminds me of a (possibly apocryphal) study I heard about where they gave healthy people a checklist of life threatening symptoms (chest pain etc) and asked them to keep a diary for a few days recording them - at the end of the study everyone had recorded 1 or 2 potentially life threatening symptoms per day.

The question is, does everyone with a positive Rose angina questionnaire have true angina and thus CHD? Now obviously a questionnaire that asks about chest pain is going to pick up people with angina (angina being, by definition, a form of self-reported chest pain that meets certain criteria) but it appears that some 70% of people diagnosed with CHD via the Rose questionnaire in the Whitehall II trial did not have a formal diagnosis of angina - that is they had not been diagnosed by a doctor with angina and did not have documented CHD through any other means. The risk here has to be that at least some of those 70% did not have angina at all - only about 12% of these people had an abnormal ECG, 5yrs later 80% still hadn't been diagnosed with CHD by a doctor, 15% didn't even report any further anginal symptoms, and 50% still didn't have any evidence of CHD other than via the Rose questionnaire.*5

So most studies have tended to find associations only between subjective reports of psychosocial factors (such as job control but similar problems are found in studies of other 'psychosocial' risk factors) and subjective measures of cardiovascular disease (the Rose questionnaire), rather than objective measures (like documented MI). We really have to entertain the possibility that people report more symptoms of chest pain when they feel less in control of their work (causality here may be direct, or via third factors like personality) without necessarily actually having increased rates of CHD - that is they report more chest pain for psychological reasons without necessarily having increased rates of dodgy coronary vessels in the heart. Without an effect on objective coronary endpoints we can only assume that an explanation of this form is most likely.

Just as we discussed in part 1, this criticism of the Whitehall II results is far from a novel observation, in 2005 epidemiologist George Davey Smith noted the results from one of his own studies using the Rose angina questionnaire:

"The large apparent influence of stress on incident angina was probably seen because the people who reported high stress also reported other forms of discomfort in their lives, including chest pain. This was obviously not due to there being any actual stress-related coronary disease, otherwise it would have been revealed in incident ischaemia and cardiovascular disease mortality.A question of emphasis

...

We could have published the 2.5-fold increased risk of angina independent of confounders and reporting tendency, because studies of stress have got into major journals reporting on just this outcome with similar effect sizes...Rather than this, we reported these results as demonstrating how it is possible to get misleading findings on stress and disease from observational epidemiology. It is interesting to compare our results...with the Whitehall II study findings for job control...The two studies got very similar results with a subjective measure - Rose angina. In both studies there was no association between job control and the non-subjective measure of electrocardiogram (ECG) ischaemia. There is a remarkable parallelism between the findings."

To sum up part 2 - Wilkinson & Pickett rely very much on a psychosocial explanation of how inequality can impact on health and other aspects of quality of life without being mediated via material mechanism such as wealth or healh expenditure. While superficially plausible the basis for this explanation remains, at the very least, unproven. My concern is that if you purely emphasise the psychological impact of inequality then you are choosing to ignore or minimise (and in places W&P explicitly do this) material inequality and will encourage the rejection of more concrete concerns such as addressing smoking behaviour or increasing healthcare expenditure - things which will have a real impact on health and quality of life and which are probably going to be easier to provoke the necessary political will to address directly than tackling the hypothetical ill-effects suffered by people's perception of status inequality.

So what is my overall conclusion from reading the book? Well I said when I started out writing these two posts that I avoided reading the book for a long time because I both (a) sympathised with the authors aims and broad policy recommendations and (b) suspected that the actual data and methods used would make me cringe and then rant. I think I was proven right in my (b) but I also think that exposure to the arguments of W&P has undermined my belief in (a) - not that I now think inequality is good but rather that maybe I was wrong about sympathising with W&P's aims, because I wonder whether they are really quite so similar to mine after all.

As I concluded at the end of part 1, I don't think the Spirit Level deals with confounding factors at all adequately - and I think this it driven by a desire to undermine any causal role of material factors in explaning the relationship between inequality and health or other societal ills. This leads to W&P making what seem to be arbitrary and suspect looking decisions to exclude countries from their analyses or to use specific data sources rather than others precisely to undermine the relationships between material factors and these important outcomes.

They rely heavily on the unproven psychosocial hypothesis to provide a causal underpinning to the associations they describe despite this model being derived from a flawed interpretation of studies such as Whitehall II. I think that there is a real danger that the Spirit Level will lead people who genuinely recognise the social ills caused by inequality in society to neglecting real material changes that could be instituted in the here and now, and encourage politicians to ignore those changes because we all know that it isn't things like relative poverty or lack of access to healthcare that causes these societal problems, it is the psychological trauma of perceiving that you are lower status than someone else. In this regard I think that the Spirit Level may actually have a rather pernicious effect in undermining the very measures that we should be championing to address the inequality we see in our society today. This leads to my concern that perhaps I don't subscribe to (a) above because the authors aims and broad policy recommendations could actually conflict with those I would advocate from a neo-materialist perspective.

A worrying further point that I haven't discussed (largely because W&P simply do not provide much evidence to elaborate on it)*6 is that the Spirit Level, particularly in its media guise, has also set itself up for failure - W&P have framed the debate in such a way that they argue that inequality in society leads to worse outcomes for the whole of society, not just those at the bottom of the socioecenomic gradient. Now that may well be true for a number of social ills, but it may also not be for a number of other outcomes. By framing the debate as one of selfishness rather than altruism it provides a get out clause for those better off in society from supporting increased equality if they come to find that inequality is not always disadvantageous for them personally.

* The story of the discovery of the relationship between H. pylori and peptic ulcers is rather well know but it is a salutory lesson that spending too much time worrying about stress as a cause for disease can lead us to neglect rather stronger and more easily remedied physical causes.

** However there is actually only pretty equivocal evidence for an effect of the psychosocial environment on cortisol levels:

"In the 23 studies addressing association between cortisol in serum or urine and the psychosocial working environment, no consistent results were found: 11 showed no association, nine showed a positive association and three showed a negative association."

*** The latest data from the Whitehall II study show that, while those in the lowest employment grade compared to the highest group had 1.6x the death rate, once all health related behaviours (e.g. smoking) were controlled for, and crucially, taking into account how these behaviours varied over the course of the study, there was no statistically significant increase in the overall death rate in the lowest grade compared to the highest. However, overall there was a 1.85x rate of death from CVD in the lowest job grade, but no increased rate of non-CVD mortality. Therefore the main focus of those studying the relationship between inequality and health is on cardiovascular disease, and this has indeed been associated with levels of the 'stress hormone' cortisol as I noted above.

*4 The specific figures from these two studies are reproduced below with the more objective CHD outcomes in bold:

- In Bosma et al 1997 (from Table 6) odd ratio (OR) of new CHD at follow-up comparing low job control versus high job control: all CHD 1.93 (95% confidence interval 1.34-2.77) and adjusted for coronary risk factors (CRFs) 1.99 (1.36-2.91), angina 2.09 (1.29-3.37) and adjusted for CRFs 2.02 (1.22 to 3.34), diagnosed IHD 1.49 (0.81 to 2.74) and adjusted for CRFs 1.26 (0.67 to 2.39).

- In Kuper & Marmot 2003 (from Table 2) hazard ratio (HR) of new CHD at follow-up comparing low job control versus high job control (men only): all CHD 1.55 (1.26-1.90) and adjusted for CRFs 1.43 (1.15 to 1.78), fatal CHD and non-fatal MI combined 1.14 (0.82 to 1.59) and adjusted for CRFs 1.01 (0.70 to 1.45).

*6 For instance, they don't consider how things like murder rates differentially affect each end of the income distribution, assuming they're just a bad thing for society overall - which may be true but I'm pretty sure you'll find individuals doing rather well out of inequality.