I'd like to discuss the reasons for the poor employment rate of those with mental illness, why mental ill-health now accounts for such a large proportion of incapacity benefit, what can be done to help those with mental illness back into work and what impact Labour's proposed reform of the incapacity benefit system is likely to have.

Introduction

There are around 2.7 million people receiving incapacity benefits in the UK (more than a trebling since 1979). These consist of ‘Incapacity Benefit’ proper (1.4 million), the main contributory benefit for those incapable of work because of illness or disability and with sufficient National Insurance contributions, and those receiving income support (1 million) or the legacy benefit ‘Severe Disablement Allowance’ (.3 million). Around half of IB claimants are over 50 (1.3 million) with equal proportions of men and women by age, except that women retire five years earlier at 60, so there is a greater overall number of men (although the retirement age for women will rise to 65 in the future), and they are more likely to be getting the contributory benefit. There is a view that IB claimant numbers will fall away through time as a cohort of older claimants reaches state pension age because a large part of this cohort is made up of older men who were made redundant during the wave of industrial job losses in the '80s. But projections suggest that there will be no fall over the next 10 years given existing stocks and flows.

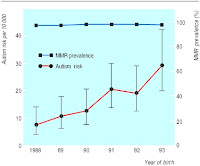

The proportion of incapacity benefit claimants with mental ill-health as their main disability has increased steadily over the last ten years from a quarter of claimants in 1996 to over 40% of claimants in 2006, with a further 10% of claimants with mental illness as a secondary factor. This has also been accompanied by an increasing proportion of the working age population claiming incapacity benefits, rising from 2% in the 1970s to 7% today (figure top right - proportion of working age population in receipt of incapacity benefits from ref [2]), a continuation of a trend since the 1950s in sickness pay generally [8]. Although inflows onto incapacity benefits have fallen 40% over the last decade this has been offset by a 35% reduction in outflows, resulting in only a small net decline in claimants.

The Government has been noticeably successful in reducing levels of those on unemployment benefit since 1997, through a combination of welfare reform and a favourable economic climate. Incapacity claims, however, have continued to rise; now representing the largest group of working age benefit claimants without employment. There are currently more mentally ill people drawing incapacity benefit than there are unemployed people on Jobseeker’s Allowance, resulting in an overall cost to the Exchequer of £10 billion.

In the non-disabled population some 80% of people are employed and only 4% dependent on benefits. For people with a disability the employment rate is 50%, but those with mental illness have the lowest employment rate of any disabled group (with the exception of learning disabilities) at 20%. Therefore two-thirds of people with mental ill-health are dependent on state benefits, compared with one-third of disabled people in general. It has been estimated that the reduced employment rate of those with mental illness costs another £10 billion in lost productivity [6].

Apart from the direct financial costs of reduced employment there is evidence that unemployment is generally harmful to health, particularly mental health. Conversely, return to employment is associated with improved general and mental health. Paid employment offers financial, psychological and social benefits to people with mental health problems that can facilitate psychological recovery and symptom reduction.

Mental illness and employment

One way to think about incapacity benefit claimants with mental ill-health is as a subset of all people with mental illness. As mentioned above, people with mental illness have very low rates of employment, and, according to the Psychiatric Morbidity Survey, some 16% of adults of working age have a mental illness, of whom up to a half are seriously ill. Unemployment rates for those with serious mental health problems range from 60% to over 95%. Thus, it is not surprising that people with mental health problems make up a significant proportion of those claiming incapacity benefit. This high unemployment is at least partly due to social factors such as stigma in addition to the direct consequences of mental health problems on the ability to work.

There are potentially two approaches to the problem of low employment for those with mental illness. The first is to tackle mental illness directly, and the other is to improve the employment prospects of those with mental illness. The former is beyond the scope of this discussion but it is worth noting that the majority of NHS resources for mental illness go to the 1% of the population with psychotic illness. Only around half of depressed patients receive any treatment and less than 10% have seen a psychiatrist.

Given the evidence for the efficacy of pharmacological and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in conditions such as depression and anxiety it has been argued that expanding the provision of therapy, particularly CBT where waiting times are currently very long, will result in substantial cost savings due to increased productivity as well as reduced suffering and morbidity [6]. Certainly GPs should consider initiating treatment in anyone that they are signing off work on mental health grounds. In studies of those with mental illness who manage to return to work from incapacity benefit almost all report that improvement in their mental health was a major factor, whether this be due to medication, therapy, or resolution of underlying stressors, and in those claiming incapacity benefit those with mental ill-health are the most likely to regard their condition as improving [9].

It has long been recognised that people with severe mental illness require help to re-enter the workforce. Pre-vocational training provides a period of preparation before entering into competitive employment. Work projects have long been utilised as a route into the labour market for people with mental health problems. Sheltered work creates part-time jobs, with low ‘therapeutic’ pay that doesn’t affect entitlement to benefits. This approach has a long history but is associated with relatively poor quality products and conditions and infrequent transition into paid employment.

Alternative models have attempted to formulate something of a halfway house between sheltered employment and the open market but supported employment programmes seek to facilitate the employment of people directly in the open workforce with market pay and conditions. This approach places people into jobs without extended preparation but provides support during employment such as for reasonable adjustments in the workplace. Studies from the US have shown supported employment to be more effective than pre-vocational training in helping people with severe mental illness to obtain employment in the open market at similar cost [5] and this result has been replicated in a European RCT [4]. This supports the use of supported employment programmes in facilitating the employment of those with severe mental illness and suggests consideration of this model for those with less severe forms of mental ill-health.

Incapacity benefit and mental ill-health

An alternative way to consider people on incapacity benefits with mental ill-health is as a subset of those claiming incapacity benefit overall.

Many reasons have been posited for the growth in incapacity benefit claimants over time. It has long been proposed that the impoverishment of old industrial areas is a causal factor. There are also suspicions that governments have used the higher payments of incapacity benefit as an incentive to reduce the headline numbers of those claiming unemployment benefit through transition to incapacity.

Along with this post-industrialisation the labour market has changed with an increasing predominance of low paid jobs with few prospects, many of which are part-time or temporary, resulting in poor employment stability and a tendency to enter and exit the labour market more frequently. For those claimants on benefits for a long time there is also now a mismatch between their perceptions of the workplace and the reality and they may need considerable help to prepare them to re-enter the workforce.

Evidence suggests that the state of the local labour market has a strong effect on the likelihood of disabled people working and it has been estimated that up to 40% of incapacity benefit claimants could be ‘hidden unemployed’ based on underlying rates of incapacitating ill health and the incapacity benefit claimant rates in areas of full employment. This would support the use of macroeconomic tools to improve the conditions in the labour market to encourage those with mental illness to re-enter employment. However, the creation of nearly two million new jobs between 1997 and 2005 was not associated with a fall in incapacity benefit claimants and other sources of labour filled the gap. Therefore, even if incapacity benefit claimant levels represent underlying economic trends, it may well require more than simply reversing these trends at a national level to tackle incapacity benefit levels.

The increasing proportion of incapacity benefit claimants with mental illness is due both to people with mental health problems leaving incapacity benefits more slowly than those with other disabilities as well as a relatively high proportion of new claimants with mental illness. The increasing contribution of mental illness to incapacity benefit claims is primarily in ‘depressive and neurotic’ conditions rather than psychoses which have remained fairly stable in incidence (and thus fallen as a proportion of claims) [8]. Consistent with the view that increasing incapacity benefit claims are the result of wider socioeconomic factors, rather than mental ill-health per se, the increase in claimants with mental ill-health has occurred despite no apparent increase in the prevalence of mental disorders (except for alcohol dependence) in the wider community. Similarly, the wide variations in numbers of incapacity benefit claims, where the North of England, Scotland and Wales have rates double that of the South of England is not reflected in the underlying prevalence of mental illness in those populations.

Ninety percent of people who start claiming incapacity benefit expect to return to work, and around 60% of people starting on incapacity benefit stop claiming within a year. However, once on incapacity benefit those that expect never to leave it trebles, and those that stay on benefits for more than two years are more likely to retire or die than get another job. This compares to less than 5 per cent of those on unemployment benefits who have been claiming for over five years. More adults with long-term mental health problems report that they wish to return to work than people with other disabilities, yet evidence from welfare to work programmes such as the New Deal for Disabled People and Pathways to Work suggests that people with mental health conditions have not been helped to the same extent as those with physical illness.

The bulk of incapacity benefit claimants are aged over 50yrs but the prevalence of mental health problems in claimants is highest among younger claimants. Of recent applicants for incapacity benefit those with mental ill-health are less likely to be currently working or to have a job to return to than other applicants. They are also more likely to say that they have low confidence about working, that they will need help, rehabilitation or other assistance before they could consider working, that they are unlikely to get a job due to their sickness record, and that they would be financially worse off if they got a job. Recent claimants with mental health problems were twice as likely as those with only physical conditions to report that they had problems with numeracy or literacy [9].

Even among those claming incapacity benefit for conditions other than mental health problems reported depression, stress, and anxiety are very high. In fact many of those claiming incapacity benefit with mental illness as their main condition also have a physical illness (although this could partly be due to the greater emphasis on physical conditions under the current capability assessment questionnaire) and those with comorbid physical and mental illness are more likely than those with physical or mental illness alone to fail to return to work. Studies have demonstrated a link between poverty and mental illness, with poverty causing mental ill-health as well as being a consequence, including through reduced standards of living causing depression and anxiety. Many people entering incapacity benefit do not come via employment but rather other benefits and it is conceivable that they have developed mental health problems at least in part due to the stresses of unemployment and poverty. The prevalence of mental ill-health is also especially high for people entering incapacity benefit who have been recently care-giving or looking after the home or children.

There is a strong interaction between physical and mental illness (such as the transition from acute to chronic back pain) and it is possible that poor management of physical illness could contribute to the emergence of depression and anxiety through loss of social roles, isolation, and poverty. Government trials of early access to psychological therapy have produced a 5% reduction in patients claiming sick pay through returning people to work [2].

There is evidence for an association between poor mental health and factors in the workplace such as long hours and workload and interventions use training and organisational approaches to increase support or participation in decision making can improve psychological health and levels of sickness absence [7]. Few people regard works stress as the sole trigger of their mental ill health but it is commonly cited as an exacerbating factor. Some people moving onto incapacity benefit with mental ill-health from work report having requested amelioration of work stress but none of these explicitly related these requests to mental health problems [9]. This highlights the reluctance of people to communicate their mental health problems to employers. When an employee develops a mental health problem they may initially exhibit reduced job performance which can cause loss of job satisfaction causing further decline in mental health.

Around two-thirds of those entering incapacity benefit with mental ill-health from employment regard the loss of their job as being due to their mental illness, while 20% say it was due to other unrelated factors (such as termination of contract) [9]. The period of sick leave before transition to incapacity benefit is likely to be a critical period and most people have not discussed their mental health problems with their employer at this point. It is therefore worth considering early intervention at this stage to try and prevent transition from sick leave onto incapacity benefit and to facilitate communication between health services, employee and employer.

A high proportion of incapacity benefit claimants with mental health problems report that their problems fluctuate over time, particularly in comparison to those with physical illness, and they are more likely to be younger and have characteristics that disadvantage them in gaining employment such as no recent employment, a poor work history, and minimal qualifications. Employers particularly discriminate against a history of long-term sick leave and are half as likely to say they would employ someone with a mental illness compared to someone with a physical illness.

Around a third of entrants onto incapacity benefit are not claiming for the first time, and a third have received unemployment benefit in the last two years. People with mental health problems are less likely to have moved onto incapacity benefit via work than other claimants, and this suggests that there is a considerable degree of movement into and out of incapacity benefit and employment and that this could be worse for those with mental illness due to their fluctuating course and adverse work history.

Fluctuating illness makes it difficult to return to work and difficult to reclaim benefits when leaving work again. The benefits system is not designed to cope with this other than in the short term and job retention may be facilitated by giving disabled people in employment a right to temporary leave to allow them time for rehabilitation support with a guaranteed return to work.

Problems with the incapacity benefits system include a failure to prevent people from moving onto incapacity benefits, benefits trapping people into dependency with financial disincentives to finding work or training, the likelihood of leaving benefits rapidly decreasing over time as people become disconnected from the workplace, financial incentives to stay on benefits for longer (incapacity benefit rates increase over time), and a lack of support for moving into employment.

Government reforms

The Government aims to reduce incapacity benefits claimants by one million from 2.7 million to 1.7 million over the 10 years from 2006 to 2015. It is using a combination of anti-discrimination legislation and reform of the benefit and employment systems to try and tackle incapacity benefit levels [1].

A new Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) replaced incapacity benefits for new claimants in October 2008 (being rolled out to existing claimants 2009-2013), with capability reports focusing on what people can do, rather than what they cannot and the ‘Pathways to Work’ scheme being rolled out across the country with compulsory work focused interviews, ‘Condition Management Programmes’, and financial bonuses for return to work. ESA rates will be comparable to jobseeker's allowance, rather than current IB levels, with the minority exempted from seeking work qualifying for an increased rate. Evidence from trials of Pathways suggests an eight percentage point increase in the incapacity benefit off-flow rates (figure bottom right - incapacity benefit 6-month off-flow rates from ref [3]) but unfortunately this benefit is not translated through to those with mental health problems. There is an additional concern that the destination of over half of those leaving IB is unknown, and the second largest group (25%) is those transferring to another benefit, only 4% return to work. There are substantial and rapid transfers between IB and job seeker's allowance, and, of those entering work from IB, some 14% return to IB within the year.

The reasons for the failure of Pathways to help those with mental health problems return to work is unclear. It is certainly the case that these claimants have an increase in those factors with have an adverse effect on gaining employment such as a poor work history. The recurrent pattern of mental illness may also make it difficult to stay in the workplace. Although GPs have not traditionally regarded as their role to be involved in detailed discussions about employment with their patients they could be encouraged to emphasis the importance of work for well being and self esteem.

In Pathways areas a formal 'In-Work Support' programme is available but this only lasts for six months. This has not been widely taken up but could be extended to form the basis for a supported employment model similar to that seen with severe mental illness to facilitate returning to and staying in work.

The Government’s published plans [1] do not currently contain any provisions to help people to remain in work during their initial period of ill-health. Carol Black has made a number of recommendations that go beyond the governments plans for helping those on incapacity benefit back to work [2] and, in particular, she proposes an early intervention service called ‘Fit for Work’ where a GP can refer patients to a multidisciplinary team with a case manager liaising with GP and employer. This might provide exercise and physical activity along with psychological therapies, physiotherapy and occupational therapy, social services help, and occupational health interventions such as workplace assessment and modification. Currently the Government has undertaken to trial this proposal.

The Government’s published plans [1] do not currently contain any provisions to help people to remain in work during their initial period of ill-health. Carol Black has made a number of recommendations that go beyond the governments plans for helping those on incapacity benefit back to work [2] and, in particular, she proposes an early intervention service called ‘Fit for Work’ where a GP can refer patients to a multidisciplinary team with a case manager liaising with GP and employer. This might provide exercise and physical activity along with psychological therapies, physiotherapy and occupational therapy, social services help, and occupational health interventions such as workplace assessment and modification. Currently the Government has undertaken to trial this proposal.GPs generally do not have easy access to mental health specialists from either occupational health or general psychiatry and the raft of new proposals appear to place considerable further burdens on GP time and expertise. Perhaps it is time to go further than ‘Fit for Work’ and consider the establishment of a specialised state occupational health service where capability assessors are controlled and trained by the government rather than contracted out (the current capability assessment contract is with Atos Origin until 2012). This could help address the widespread concern that under the existing system of capability assessment mental health problems are inadequately assessed, underemphasised and minimally explored and thus provide minimal benefit to advisers seeking to place claimants into work.

It seems likely that mental health problems will continue to represent a major proportion of those claiming incapacity benefits, although the reasons for this are far from clear (and likely multi-factorial), but, despite some limited success in reducing IB levels of those with physical illness in trial areas, it is not obvious that current proposals are likely to have much of an impact on helping people with mental health problems into work. The current disconnection between psychiatric, social, and employment services needs to be tackled before a comprehensive and succesful attempt can be made to reverse the long standing disengagement of people with mental health problems from the workforce. As things currently stand it looks like recent welfare reforms will result in a large increase in unemployment levels amongst the mentally ill, with a consequent cut in living standards.

[1] No one written off: reforming welfare to reward responsibility. Department for Work and Pensions, TSO, 2008.

[2] Black, C., Working for a healthier tomorrow. Health, Work and Well-being Programme, TSO, 2008.

[3] Blyth, B., Incapacity Benefit reforms - Pathways to Work Pilots performance and analysis. Working Paper No 26, Department for Work and Pensions, HMSO, 2006.

[4] Burns, T., Catty, J., Becker, T., Drake, R.E., Fioritti, A., Knapp, M., Lauber, C., Rossler, W., Tomov, T., van Busschbach, J., White, S. and Wiersma, D., The effectiveness of supported employment for people with severe mental illness: a randomised controlled trial, Lancet, 370 (2007) 1146-52.

[5] Crowther, R.E., Marshall, M., Bond, G.R. and Huxley, P., Helping people with severe mental illness to obtain work: systematic review, Bmj, 322 (2001) 204-8.

[6] Layard, R., Mental Health: Britain's Biggest Social Problem? No.10 Strategy Unit Seminar on Mental Health, 2005.

[7] Michie, S. and Williams, S., Reducing work related psychological ill health and sickness absence: a systematic literature review, Occup Environ Med, 60 (2003) 3-9.

[8] Moncrieff, J. and Pomerleau, J., Trends in sickness benefits in Great Britain and the contribution of mental disorders, J Public Health Med, 22 (2000) 59-67.

[9] Sainsbury, R., Irvine, A., Aston, J., Wilson, S., Williams, C. and Sinclair, A., Mental health and employment. Research Report No 513, Department for Work and Pensions, HMSO, 2008.