I've talked a fair bit about the efficacy of antidepressants (or lack thereof) in treating major depression. I won't go into that again, but I did want to discuss something that has been neglected in that debate.

Bipolar depression

It's estimated that some 10% of people with a major depressive episode have underlying bipolar disorder - that is they'll go on to have a manic or hypomanic episode (if they haven't had one already) - and if the efficacy of antidepressants in straight major depression is controversial then bipolar depression is a minefield.

It is certainly considered that antidepressant usage alone gives a big risk of provoking a swing from a depressive to a manic episode so they would usually be used alongside a 'mood stabiliser' like lithium or an anticonvulsant, and even then there is considerable disagreement as to how much they help.

Lamotrigine in acute bipolar depression

Something that has got a lot of attention in recent years is the anticonvulsant lamotrigine. There is

good evidence for the efficacy of lamotrigine in preventing further depressive episodes in people with bipolar disorder. But recently there has been much interest in its use for treating an acute episode of depression in bipolar disorder, and this is despite the fact that it takes a considerable time to titrate up the dose to therapeutic levels (if you go by the BNF it takes 5 weeks to get to the usual dose of 200mg).

A major paper influencing people's thinking came out of Oxford by

Geddes et al in 2009. This was a meta-analysis of trials of lamotrigine in acute bipolar depressive episodes and had a considerable impact. The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT)

guidelines now recommend lamotrigine as a first-line treatment for acute bipolar depression largely on the strength of this analysis.

What they did was, apparently, contact GSK (who make lamotrigine as 'Lamictal') and get hold of all the individual patient level data from all five trials performed by the drug company and used it to perform a meta-analysis. They also identified two other studies not by GSK but didn't combine them because they didn't have any individual subject data and the trials were a crossover trial (which is difficult to correctly combine in a meta-analysis) and the other used lamotrigine as add-on to lithium therapy. They excluded data from one of the trials which had used a 50mg dose as this is generally considered subtherapeutic.

I'll concentrate on their findings using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD, 17-item version) which is very widely used in antidepressant trials (I've mentioned it before) which has a maximum of 54 points and a score greater than 18 is usually needed to be recruited into a trial as 'moderately' depressed. Again, I'll focus on two measures of outcome, 'response rate' (the proportion of patients in each arm who achieve a 50% or more reduction in their initial HRSD score) and mean difference in the final HRSD score.

If we look at the mean difference in the final HRSD score (this was adjusted for baseline severity in a regression) it was –1.01 (–2.17 to 0.14). That mean difference is not statistically significant (although using a different measure, the Montgomery–Åsberg

Depression Rating Scale, they did find a statistically significant effect), nor is it even suggesting a particularly large effect is possible (with the upper limit of the effect size around 2 points on the HRSD). This is smaller than the 1.8 point effect size reported by

Irving Kirsch's meta-analysis of 'new' antidepressants in major depression and when

I reanalysed Kirsch's data properly I (

and others) found an effect size of 2.7 points on the HRSD, just short of NICE's (arbitrary) 3 point threshold for 'clinical significance'.

So a mean improvement of 1.0 points on the HRSD is not exactly impressive - certainly it wouldn't be very good if that was a uniform single point improvement across every patient. But potentially it could represent a really big, 'clinically significant' improvement for a subset of patients - and we'd be interested in a drug that could do that.

So this is why we look at 'response rates' - what proportion of patients got 'clinically significantly' better, or 'remission rates', the proportion who score sufficiently low to count as being better. Commonly the former is defined as a 50% reduction in the score on the HRSD (or other symptom scale). We can see below (Figure 1) that significantly more patients responded in the lamotrigine group than the placebo group with a risk ratio of 1.27 (95% CI: 1.09-1.47), that is 27% more patients in the lamotrigine group showed an improvement in HRSD of 50% or more - that implies 11 patients need to be treated for one additional 'response'.

|

| Figure 1. Figure from Geddes et al - Meta-analysis of HRSD 50% response rates using individual patient data from GSK trials |

As has been

pointed out before, response rates in depression trials are slippery beasts. By calling a 50% reduction in HRSD score a 'response' to treatment you actually need to improve by less points on the HRSD if you are less depressed (and have a lower baseline score) so an improvement on exactly the same items of the HRSD could be classified as 'response' or 'no response' depending on that patient's initial severity. This also means that this measure is very vulnerable to small differences in baseline severity between the arms of a trial.* In practice response rates based on thresholding continuous variables like the HRSD (such as a 50% improvement threshold, or a threshold of 8 points for 'remission') are vulnerable to artefactual non-linear effects where very small improvements tip a few people over the threshold (something to particularly worry about if the threshold used seems a bit arbitrary anyway as you can easily pick one after the fact that amplifies any effect).

The response rates in this study are around 35% of patients in the placebo arm and 45% of those taking lamotrigine - so an increase of 10 percentage points due to lamotrigine. If we consider that, for the average patient, 50% improvement implies a minimum change of around 12 points on the HRSD the actual mean improvement of 1.0 points (and the standard deviation) seems a little small (in a back of the envelope calculation you could say that you would expect an average of 1.2 point improvement - thats 10% getting 12 points averaged over all the group). So a bit of a mixed bag I'd say.

Traditional meta-analysis versus individual patient data

A question that occurs to me is what extra information we gain from having the individual patient data? It is pretty rare to get hold of individual patient data when doing a meta-analysis, usually all we have is the overall results for each trial. Sometimes this doesn't make much difference, comparing the individual level meta-analysis by

Fournier et al of antidepressants with Kirsch et al's meta-analysis did not reveal any major differences (and these studies looked at fairly different sets of antidepressants).

I had a quick go at performing a study level meta-analysis of the GSK lamotrigine data** and found that the response rate had a relative risk of 1.22 (1.06-1.41) (Figure 2 below) which is pretty similar to the individual level data 1.27 risk ratio.

|

| Figure 2. Meta-analysis of HRSD 50% response rates from GSK per trial data |

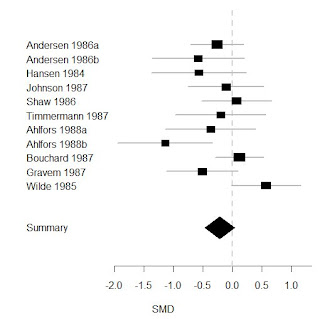

Looking at the mean difference in the change in HRSD scores I found an effect size of -.86 points (-1.84-.12) which is similar to the -1.0 effect using individual level data and is similarly also only borderline statistically significant (Figure 3 below).

|

| Figure 3. Meta-analysis of mean difference in HRSD scores from GSK per trial data |

This is pretty reassuring as it suggests the majority of the information is present in the trial data so we wouldn't lose too much or miss any important effect if we didn't have the individual patient data available. You have to ask why GSK didn't re-analyse the data themselves, this would have been easily done (it took me a few minutes). I think there are a few reasons for this, one intimated in the paper is that regulatory authorities do not accept the results of meta-analyses, they require two large positive trials for licensing a drug, and all but one of the GSK trials was negative so a meta-analysis would have done them no good with licensing. However, they could still have influenced the scientific literature or provided justification for a further larger trial and I wonder whether they didn't in fact do the same analysis as either me or Geddes et al and realise that this was probably a small and fairly dubious effect and reckon it wouldn't do them any favours in the long run.

Antidepressant response and the severity of depression

Like many previous studies of antidepressants Geddes et al also find that there is an interaction between the size of the antidepressant effect of lamotrigine and how severely depressed the patients in the study were at baseline. They found a significant interaction on their ANCOVA analysis between baseline HRSD severity and final HRSD score with a regression coefficient of .30 (p=.04). They go on to comment that:

"Thus, the interaction by severity was because of a higher response rate in the moderately ill placebo-treated group, rather than, for example, a higher response rate in the severely ill lamotrigine-treated group."

This statement is very redolent of

Kirsch et al's claim:

"The relationship between initial severity and antidepressant efficacy is attributable to decreased responsiveness to placebo among very severely depressed patients, rather than to increased responsiveness to medication."

Kirsch et al got a lot of stick for saying this, not least from yours truly, so I was interested in what a set of rather more mainstream figures in the psychiatric world (two Oxford academic psychiatrists and a psychiatrist from the GSK advisory board) were trying to say, and how this relates the Kirsch's work. Maybe I was being unfair to Kirsch?

Kirsch et al argued that the apparent increase in antidepressant efficacy with increasing baseline severity in trials was due to decreasing placebo response in more severe trials (see Figure 4 below). They further argued that this increasing efficacy was therefore only 'apparent' because the response to antidepressant was the same. I've

discussed before how, on many levels, it is meaningless to claim that this effect is only 'apparent'.

|

| Figure 4. Figure from Kirsch et al - Regression of baseline severity against standardised mean difference of HRSD score improvement for antidepressant and placebo groups using per trial data |

However, when I

re-analysed their data it was their finding of decreased placebo response that was actually only 'apparent', and was due to needlessly normalising the raw HRSD data using the standardised mean difference (see Figure 5 below) and in fact placebo responses remained fairly static with increasing severity while antidepressant responses increased.

|

| Figure 5. Regression of baseline severity against HRSD score improvement for antidepressant and placebo groups using per trial data from Kirsch et al |

Of course these correlations are only looking at the average baseline severity

between each trial and doesn't tell us whether the relationship between baseline severity and HRSD improvement holds true

within each trial for the individual patients in that trial. Fournier et al used individual level data to look at this relationship and found increases in both placebo and antidepressant responses, with the greater gradient in the latter leading to increased efficacy of antidepressants overall (see Figure 6 below) so there is actually not great evidence for a decreased placebo response with increasing baseline severity in straight trials of antidepressants in major depression.

|

| Figure 6. Figure from Fournier et al - Regression of baseline severity against HRSD score improvement for antidepressant and placebo groups using individual patient data |

So what did Geddes et al find? Well, unlike Kirsch et al and Fournier et al they primarily looked at response rates rather than mean change in HRSD, obviously you can't have an individual patient's response rate (an individual either does, or does not respond) so they divided the subjects into two groups, those with a baseline severity below 24 points, and those above. They found that only those in the 'severe' severity (>24 point) group had a statistically significant response rate greater than placebo with 46% of those on lamotrigine responding compared to 30% on placebo. In the 'moderate' (<= 24 point) group response rates were 48% for lamotrigine and 45% for placebo. Geddes and others have argued that this increased placebo response at moderate severity is due to something like inflation of baseline severity at trial recruitment (that is doctors subconsciously inflate severity for those around the lower threshold for trial recruitment and they then regress to the 'real' lower score they would have had anyway when assessed blindly as part of the trial while this doesn't happen for the more severe patients).***

Now I've outlined some of my reservations about 50% reduction in HRSD score as a measure of 'response rate' and I don't think that these numbers necessarily show what Geddes et al think it does. Let's consider a simple model of how antidepressants might work, let's say they can be modelled simply by saying that an antidepressant reduces the baseline HRSD score by

X HRSD points which is the simple sum of the placebo effect (

P) and a 'true' antidepressant effect (

A):

X = P + A

Based on this model, as discussed above, we can see how patients in the 'moderate' severity group could be more likely to respond even if

X is the same for both severity groups. This is because a lower baseline severity means less HRSD points need to be lost to reach a 50% reduction. If we take this observation it is conceivable that the lower placebo response in the 'severe' group could be, at least partly, due to pure artefact. Given that those treated with lamotrigine in the 'severe' group had a larger response rate than those on placebo you might then go on to posit that maybe

P is larger for the more severely depressed patients.

The way we ideally would want to answer this question would be to look at the mean HRSD scores as we did above for the data from Kirsch et al and Fournier et al. The response rate figures alone would still be completely consistent with a relationship like that shown in Figure 5 above and suggest that the claim that

"the interaction by severity was because of a higher response rate in the moderately ill placebo-treated group" is false.

Unfortunately Geddes et al don't show the mean HRSD data by baseline severity nor do they report the correlations between mean HRSD score and baseline severity for the lamotrigine and placebo groups separately, either of which might help to answer this question. This is a bit odd as this is one of the main areas where the individual patient data would prove very useful and answer questions that the trial only data cannot. So we'll never know whether they do or don't show that placebo responses are constant, decreased, or increased with greater severity of depression. I've reproduced the data presenting each trial below (Figures 7 & 8) but these can't really answer this question, for that we need the within trial data.

|

| Figure 7. Simple regression of mean baseline severity against 50% response rates from GSK per trial data split by lamotrigine (blue) and placebo (red) |

|

| Figure 8. Simple regression of mean baseline severity against mean change in HRSD score from GSK per trial data split by lamotrigine (blue) and placebo (red) |

Amusingly, if you consider Figure 8 in the same way as my Figure 5 and attempt to

determine a severity 'threshold' above which the NICE 3 point 'clinical significance' criteria is reached then you find that you never actually reach it.

Summary

So, what should we conclude? Well a few things:

- Lamotrigine is not very effective for acute bipolar depression

- Individual patient data in these trials doesn't tell us much more than a classical meta-analysis

- The effect of lamotrigine, like other antidepressants in major depression, increases with greater baseline severity of depression, but never reaches the NICE 'clinical significance' criteria

- It is unclear exactly why antidepressant efficacy increases in this way but it is far from established that it is due to "higher response rate in the moderately ill placebo-treated [patients], rather than, for example, a higher response rate in the severely ill lamotrigine-treated [patients]"

So what next?

So what medication should be used for acute treatment of bipolar depression? Well I think the data from quetiapine is

pretty promising and certainly a lot more convincing and impressive than for lamotrigine monotherapy. Perhaps lamotrigine will be synergistic when added to quetiapine and the first author, John Geddes, is heading up the

CEQUEL trial looking at just this question.

* I think a better measure might be a fixed improvement in HRSD score, call it a 'clinically significant response', this would avoid the assumption that antidepressants somehow cause an X% reduction in HRSD score rather than say improving Y number of symptoms, and thus the problem I've mentioned above about how mildly depressed patients need less improvement to 'respond' than more severely depressed.

** I got the response rate data from the Geddes et al paper and the HRSD mean difference data from the GSK trials register (since it wasn't presented in the paper). I used mean change scores rather than final HRSD scores (although this shouldn't make much difference), I had to estimate standard deviations for trial SCA40910 and the means for trial SCA30924 were already adjusted for baseline severity. Data are for fixed effect models but random effects makes minimal difference to the results.

*** Interestingly this explanation would only be tenable if trials of greater severity showed the same within-trial effect as trials of lower severity, since this effect should take place at the recruitment threshold irrespective of what that threshold is. So therefore within a trial the less severe subjects around the recruitment threshold should show a greater placebo response whereas there would not necessarily be any relationship between average baseline severity and average response between trials. This means that my regression data from Figure 5 above doesn't necessarily argue against this model - what we need to know is whether this relationship holds within the trials, something that even the individual subject data from Figure 6 doesn't rule out because we'd ideally have data separately plotted for each trial since the recruitment thresholds for each trial may have differed.